In 2010, as part of an experiment and learning exercise, we lived on World War II rations to see how it worked and if it was possible with today’s diet.

The answer was, yes, it was possible, but good lord it was dull and hard work.

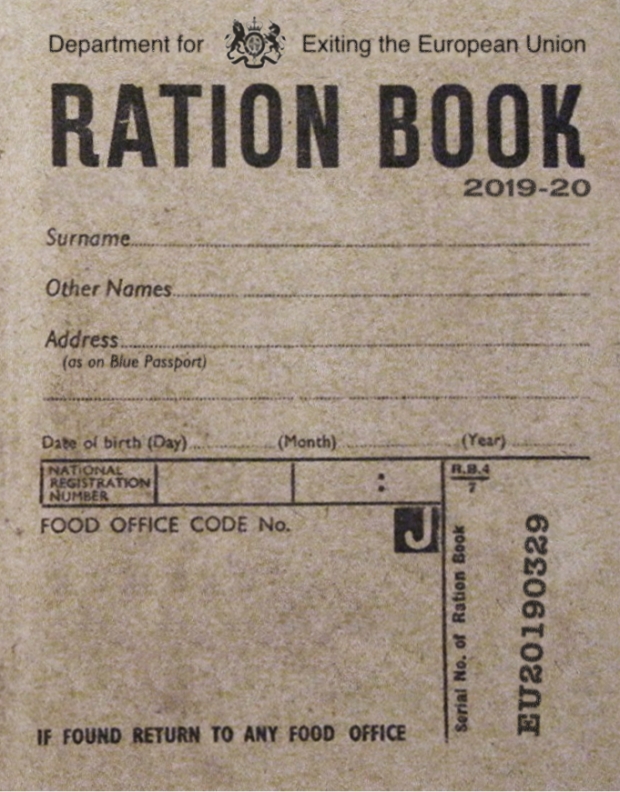

But the experience is likely to become vital. On 29 March 2019, we will leave the European Union with little or no preparation done to ensure food security. The likely results will be random shortages and hyperinflation, at least in some key commodities.

This is what civil servants in the Department for Exiting the European Union expect; many individuals there have started to build their own store cupboards of food to ensure their families don’t go hungry in the short term.

Obviously, eventually a system to allow for food distribution to begin working again will be implemented. But it’ll take at least six months and the fall of the government to happen. Even then, that system might have to include elements of rationing – if the government decides that ‘fair shares for all’ is something it wants (they’ve shown no sign of this since 2010, preferring ‘devil take the hindmost’ as their mantra).

I’ve started adding items to my weekly shopping list to put away for that particular rainy day, building a brexit store cupboard to ensure that neither of us go hungry, but trying not to panic buy or add too much to our exiting overheads.

The first problems we’ll see after brexit will be shortages/high prices for fresh goods – salads, fruit, meat. There’s nothing that can be done about that – you obviously can’t build a six-month stock of tomatoes and bananas.

But the nutrition of fresh fruit and vegetables will still be required, so tinned goods are our friend here. Tinned tomatoes make up a lot of the storage space because they are so flexible for making meals. Tinned soup, tinned vegetables and tinned fruit in juice are also there, ensuring that, if nothing else, we keep up the supply of vitamin C and fibre our bodies need.

Next up are shelf-stable carbs – pasta and rice, mainly. The average Western European eats far too many of these anyway, to the point that people try to cut them out entirely. Both extremes are foolish. Carbs are instant energy and needed in moderation by everyone. They’re also really tasty and help to bulk out a meal to create a feeling of being full at the end of a meal – useful when you’re worrying if the country will recover at all from this entirely foreseeable nightmare. Flour is there too, but mainly as a cooking ingredient because my cakes and bread are always almost inedible.

Oats and oatmeal are a great addition here, as both can be easily made into both sweet and savoury dishes and absorb the flavours around them, creating the illusion of abundance. During the rationing experiment I made a lot of meals with mince, one third actual ground beef or vegetable protein, one third finely diced mushrooms and one third oats soaked in gravy. Nobody ever realised it wasn’t plain mince beef.

If you remember your Food Pyramid from school (it’s largely almost entirely unhelpful, but it’s a good basis to start from when planning meals; the above 1946 US Department of Agriculture poster is a better option), the next tier is protein. Ours is suppled by tinned fish and meat for my husband and bags of dried textured vegetable protein (TVP) and vegan sausage and burger mix for me. The latter can be bulked out with oats; the former less so. Smaller tins are better than large ones, as wasting food by having it go off is terrible at the best of times and virtually criminal in times of shortage.

The next tier is dairy produce. This is one thing that is likely not to go into shortage in 2019, but it is very likely to jump in price quite dramatically. Dried skimmed milk is awful, but it’ll do as a cooking ingredient. The Americans, no slouches when it comes to shelf-stable awful food, do various long-life cheese powders. By combining the dried milk with a good shake of a strong cheese powder, you’ve got an entirely passable cheese sauce, with which culinary miracles can be made.

At the top of the pyramid is butter and spread. These are not shelf-stable; there is such a thing as tinned butter, but that’s basically unfiltered ghee and is awful in almost everything. I’ve invested in lots of small bottles of oil – olive and rapeseed mainly – for cooking and for dipping and frying bread in. Small bottles because, once opened, the shelf life reduces dramatically. Buy small bottles you can open and go through rather than bulk containers that may perish before you’ve finished them.

There’s a temptation, especially if doing a brexit cupboard shop online, to buy condiments and those little flourishes – sauces, chutneys, condiments – that make food extra exciting. The actual experience of World War II suggests these are foolish buys. During the entire War, Fortnum’s and other such emporia were fully stocked with things like mint sauce and ketchup and stock cubes and all those other bits and pieces, often at very reasonable prices even at the worst of the Wolf Packs in the Atlantic. They were no use whatsoever without the main meal they do so much to enhance – you try having a cheese and pickle sandwich without the cheese, the butter or the bread, or mint sauce on a plate with no lamb or potatoes, and report back to me on how good it was.

We have 290 days, at the time of writing, to build up this cupboard. By adding items to our standard weekly shop, the cost should be ameliorated. If brexit is a success – please, I know already – then we’ll end up with a cupboard full of useable if dull foodstuffs to eat over the course of 2019.

Otherwise, at least we won’t go hungry while we take back control.